Former Binance CEO Qiao Changpeng (CZ) recently said that the UAE generates surplus electricity to meet “three days” of high demand each year, making Bitcoin the last buyer of energy that would go unused.

Stripping away the details, the logic holds that mining turns curtailed or pent-up power into revenue when other off-takers don't want it.

The question in 2026 is not whether the surplus can be mined, but whether that surplus is structural enough to shrink, and whether miners can maintain their position as AI and high-performance computing drive up the clearing price of firm supply.

Economics is straightforward. According to the Cambridge Digital Mining Industry Report, electricity accounts for more than 80% of miners’ cash operating expenses.

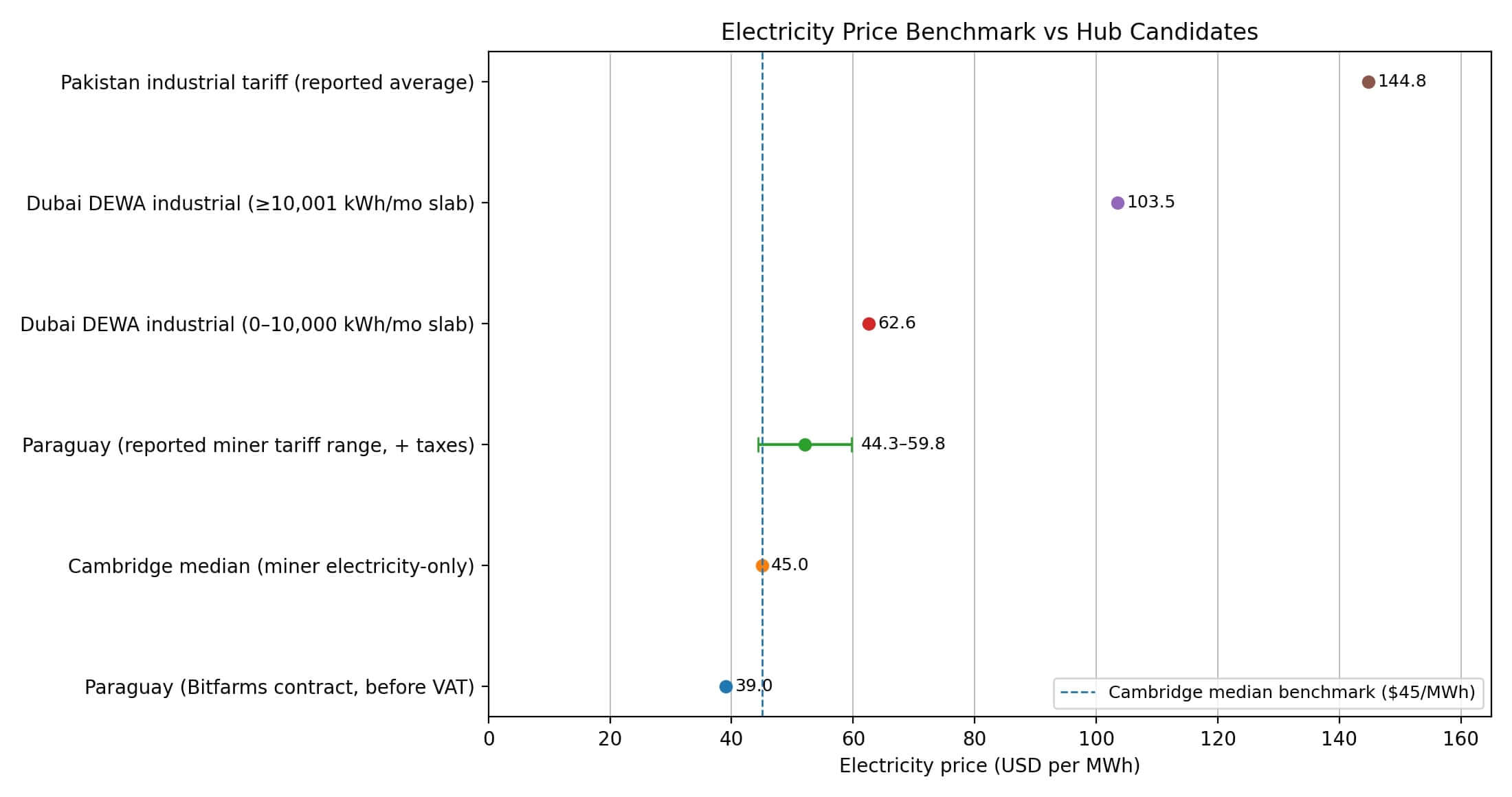

The report notes that the median electricity-only cost is about $45 per megawatt-hour, and notes that surveyed miners shed 888 gigawatt-hours of load in 2023, which equates to about 101 megawatts of average pendency capacity.

This reduction figure supports the flexible load theory. That means miners can turn off power if the grid needs relief or prices spike, helping power companies manage intermittency and congestion.

Geography tells the rest. Though an imperfect methodology, Cambridge's Bitcoin Power Consumption Index Mining Map tracks where hashrate is concentrated, but there are caveats to the data, including a one- to three-month lag in predictions and the potential for VPNs and proxy routing to drive up the share of countries such as Germany and Ireland.

Country attribution depends on the geolocation of the IP address. This is a method that is sensitive to routing behavior and subject to other inference limitations.

Within these constraints, this map shows mining distributed across jurisdictions, but with one thing in common: It's access to cheap power, stranded power, or both.

Pakistan turns excess capacity into policy

Pakistan made the most obvious bet. The government has announced plans to allocate 2,000 megawatts in the first phase of a national initiative to be split into Bitcoin mining and AI data centers, and CZ has been appointed as strategic advisor to the Pakistan Crypto Council.

The Treasury framed this as a way to monetize surplus generation in energy-surplus regions and turn underutilized capacity into tradable assets.

Continuous operation of 2,000 megawatts produces 17.52 terawatt-hours of electricity per year. Modern mining fleets operate at 15 to 25 joules per terahash, and their power can theoretically support hashrates of 80 to 133 exahashes per second before considering reductions, power usage efficiency, or downtime.

Size is not as important as structure.

What type of contracts will miners sign, interruptible baseload or fixed baseload? Which regions will be chosen and how long will the policy last if tariffs rise or IMF pressure increases?

Pakistan's vision suggests that “surplus electrons” could become a national export, but whether the 2,000 megawatts materializes as a hub or just a headline depends on execution.

Surplus by design, not by chance

The UAE's opportunities are not forever in surplus, but they are in surplus by design.

Dubai's peak demand reached 10.76 GW in 2024, an increase of 3.4% year-on-year, concentrated in the summer months when cooling accounts for most of the load.

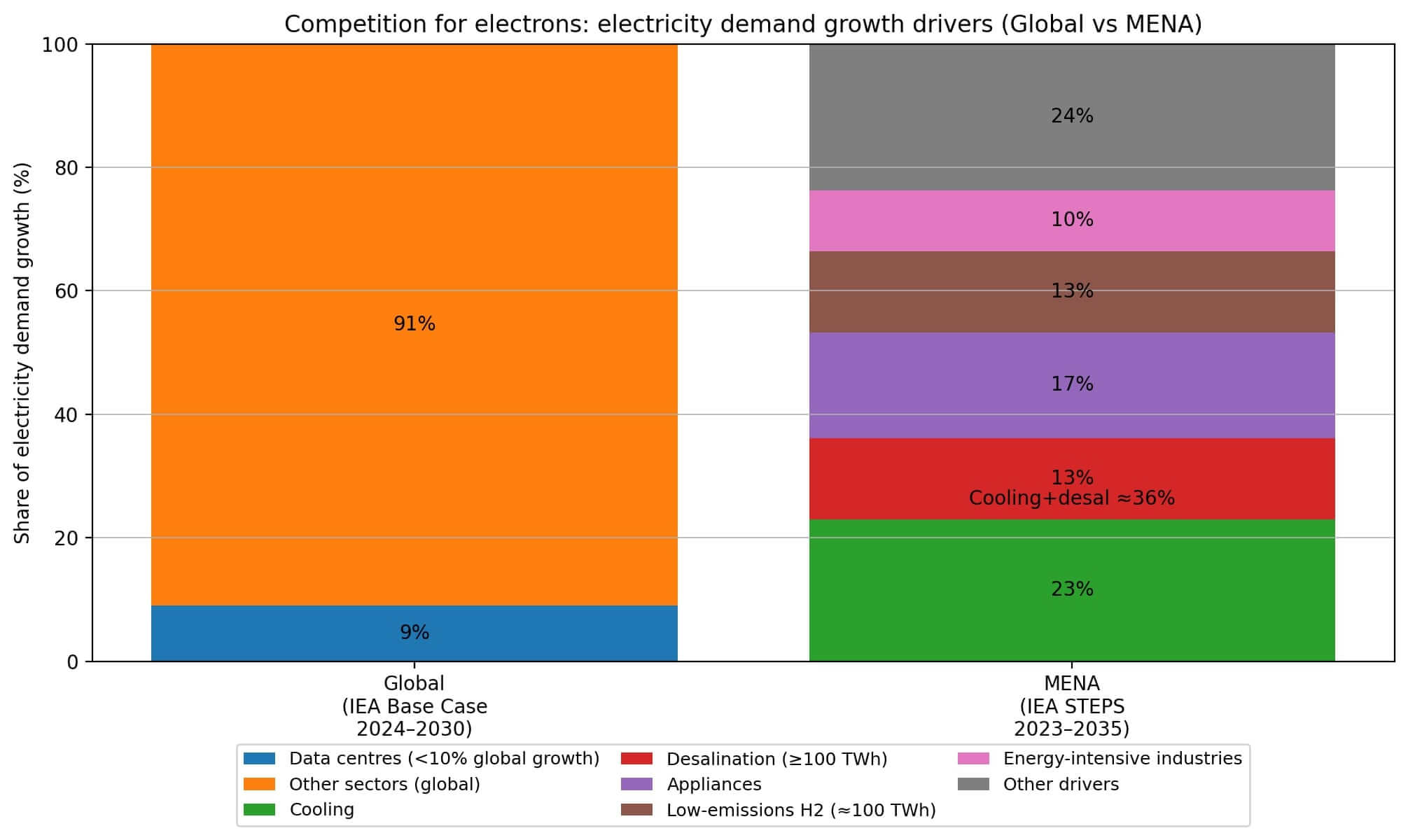

The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that cooling and desalination will account for nearly 40% of electricity demand growth in the Middle East and North Africa by 2035, explicitly naming data centers as another growing source of load.

This creates special opportunities for miners. Utilities are building systems to handle summer peaks, but require year-round monetization, normalization, and off-peak grid stability.

Miners win when they can offer more flexibility than AI and HPC buyers, such as curtailment-aware loads that absorb power that others cannot accept due to location, congestion, or dispatch constraints.

While Bitcoin miners can be switched off instantly, data centers require continuous operation, making reduction and grid management much more difficult.

The region's ramp-up trends favor baseload capacity above seasonal demand, but the IEA's same outlook marking data centers as demand drivers means miners face direct competition for the electrons they need.

The case for hubs will depend on whether there is enough value for utilities to price dispatchable loads at an attractive price, or whether a firm offtake agreement with an AI buyer will shut out mining altogether.

If a battle for surplus occurs

Paraguay shows what happens when surplus electricity attracts miners, causing a backlash.

The country's hydropower capacity attracted operators looking for cheap electricity, but rate changes have come at a cost. Miners are now reportedly paying between $44.34 and $59.76 per megawatt hour in taxes, and local industry sources say 35 companies have ceased operations after the price hike.

Law No. 7300 strengthened penalties for power theft related to illegal cryptocurrency mining, increasing the maximum penalty to 10 years and authorizing the confiscation of equipment.

Despite this, real capital continues to flow. HIVE has completed Phase 1 infrastructure of a 100-megawatt facility backed by a fully powered 200-megawatt substation, demonstrating that some operators are considering durable economics even after repricing.

The tension in the relationship is clear. Hydropower surpluses generate initial customer attraction, but as mining companies scale up and realize that they are intensive, taxable off-takers, or when local grid constraints or noise externalities increase political pressure, states reprice electricity.

Paraguay's trajectory shows how hubs flip when their social license expires, making policy durability the primary variable in the site selection model.

What actually makes the hub

Mining hub viability in 2026 will come down to the formula: delivery cost per megawatt hour x contract flexibility x policy durability, measured against what AI and HPC buyers are willing to pay, grid deficiencies, and foreign exchange and import frictions.

Three scenarios are developed regarding these variables.

The first is that the oversupply caused by restraint will persist. That means renewable energy is added faster than the grid can absorb it, curtailment increases, and miners profit from flexible demand. Hubs are most likely to be jurisdictions with weak transmission, hydropower or seasonal surpluses, such as Paraguay, or countries that explicitly monetize excess capacity, such as Pakistan.

In the second, AI competes for power with corporations over miners. Data centers require long-term, stable supply, leaving miners prone to interruptions, congestion, and stranded situations. Hubs will emerge where miners can access interruptible pricing and “non-exportable” energy, rather than the capabilities of major companies.

In the third, political retribution and backlash change the game. As miners expand in size or create shortages or noise at home, governments raise rates. Paraguay is the template. The hub is turned upside down when the economics that attracted the miners are recalibrated by the same state that built them.

The IEA framework is important here. Global electricity demand is expected to grow at approximately 4% annually until 2027, driven by industrial production, air conditioning, electrification, and data centers.

Renewable energy capacity additions are accelerating, but grid integration has been slow. This delay creates throttling and congestion that miners can monetize, but it also means that surplus is a moving target.

The hubs that survive until 2026 will not only be in jurisdictions where power is cheap, but also where power cuts and congestion are likely to persist, where regulations allow mining as a dispatchable load, and where miners can compete with or complement AI and HPC for electrons.

checklist

Six variables determine whether a jurisdiction becomes a mining hub or just a headliner.

The surplus type is the first. Is it hydro seasonality, stranded gas, flaring mitigation, or off-peak nuclear baseload? Each has different persistence and shrinkage.

Delivery cost and contract structure follow as the second variables. What is the total price per megawatt hour? Also, is the contract breakable? Who bears the congestion risk and is there any compensation for congestion?

Next, ASIC import and logistics are important, such as customs duties, transportation lanes, spare parts availability, and capital management, all of which impact speed-to-market and operational risk.

Policy durability is the fourth variable. Rate revision risk, licensing requirements, surprise bans, and theft crackdowns will determine whether a hub remains a hub.

Climate, cooling and water also play a role. Air cooling limitations, immersion feasibility, and heat and noise externalities limit where large-scale operations can be carried out without provoking local opposition.

The final variable is offtake competition. Growth in demand for AI and HPC is now clearly reflected in power demand forecasts. Hubs need to anticipate competition not only for cheap electrons but also for “good electrons.”

Pakistan's 2,000 MW plan is the clearest indication that the government sees surplus electricity as an exportable asset class and mining as one means of monetizing it.

Whether that path leads to the next major hub in 2026 will depend on execution, including contract terms, site selection, and whether political agreements hold as miners begin consuming gigawatt hours at scale.

CZ's theory about Bitcoin as the buyer of last resort is correct in principle. The practice is even more troubling, relying on power grids that can't absorb renewable energy fast enough, states that allow flexible loads, and miners that can remain competitive as data centers drive up the price of stable power.

The sites that emerge will be those that have had these conditions in place long enough to build infrastructure and enter into contracts that will survive the first rate changes and the first summer power outages.